Nan Grogan Orrock defied her family's wishes by sneaking away to join the 1963 March on Washington. But don't ask her about Martin Luther King's "I Have a Dream" speech. She doesn't remember it.

She was struck by something else.

Orrock was stunned by the marchers. They nonchalantly told her they had been fired from their jobs, forced from their homes and beaten and jailed for joining the movement.

A white student at a women's college in Virginia, Orrock had ignored the movement until then; she'd been taught by her fellow Southerners that civil rights were "somebody else's business that had nothing to do with me."

"The highlight of the day was not his speech," says Orrock, now a Democratic senator in the Georgia legislature. "My mind was on fire from all that I was seeing and hearing. I realized that I was in the presence of great courage. I resolved that day that I was going to be a part of this."

The story behind 'I Have A Dream' speech

When the country commemorates the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington on August 28, some will ask if the nation needs another civil rights movement today. Here's another question: What makes a movement work in the first place? Why do some movements like the struggle for civil rights take off while others like Occupy Wall Street wilt?

Orrock's story suggests that it's not just the big moments -- the charismatic leader and the thrilling speech -- that make a movement work. There are those tiny moments, such as ordinary people sharing their stories of quiet courage with outsiders, that are just as crucial. What are the ingredients that any successful movement needs?

There is a secret sauce for the weak to beat the strong, say those who have studied and participated in successful nonviolent social movements. The lessons from the March on Washington and other movements throughout history offer clues. If you want to take on the forces of power and privilege known in some circles as "The Man," they say, you must remember four rules:

1. Don't Get Seduced By Spontaneity

Spontaneity is sexy. The urge to act on an irrepressible urge can inspire others. A Tunisian street vendor who set himself on fire is credited with starting the Arab Spring. And who can forget the lone man who stood in front of a column of tanks in Tiananmen Square during the pro-democracy protests in China in 1989?

Tunisian protests set off the Arab Spring,

a series of uprisings in 2011.

A spontaneous act gave the March on Washington its most memorable moment. King's "I Have a Dream" riff wasn't in his written speech. He improvised it after he completed his written speech sooner than he had planned and a gospel singer behind yelled, "Tell them about the dream."

Yet spontaneity is overrated, some observers say. Successful movements are built on years of planning, trial and error, honing strategies for change. A good movement should already have an organizational structure set up to take advantage of a spontaneous act that grips the public.

Some movements stage their own "spontaneous" acts.

Remember Rosa Parks? Schoolchildren are taught that Rosa Parks was the quiet, bespectacled black woman who sparked the civil rights movement when she spontaneously decided one day that she was not going to move to the back of a segregated bus.

It's a good story but bad history. Parks had been carefully chosen for that moment. The woman who looked so docile in the historical photographs was actually a tough, seasoned civil rights activist who had been with the NAACP for 12 years and had attended an elite training school for civil rights and labor activists.

Parks was just one in a line of several black women chosen to stage "spontaneous" sit-ins on segregated buses, says Parker J. Palmer, author of "Healing the Heart of Democracy."

"Six or seven black women had done what Parks had done before and had simply been ticketed or arrested and certainly did not make history," Palmer says. "I can guarantee you when Parks sat down on that bus where she ought not to, she had no guarantee that this was going to work out. In that moment, she felt very alone."

Parks attracted attention because her arrest could not be ignored, historians say. The other women arrested were unmarried or single mothers who could be caricatured by segregationists as women of ill repute. Parks was a married seamstress who was respected in her community.

"She could not be thrown in jail and forgotten and there would be no publicity," says Jerald Podair, a history professor at Lawrence University in Wisconsin. "She had been preparing for that moment her entire life."

A contemporary movement in North Carolina also reveals how deceptive the idea of "spontaneous" can be.

The movement has been called Moral Mondays. News accounts say it began in February when 17 people were arrested in Raleigh, North Carolina, while protesting the policies of a new Republican-led state legislature. At least 900 people have since been arrested during weekly protests over everything from the legislature's decision to cut teachers' pay and unemployment benefits to its rejection of expanded medical coverage for the poor and underinsured under Obamacare.

Much of the news coverage describes Moral Mondays as a spontaneous reaction to the legislature's decisions. But the coalition driving the protests actually formed years ago to be a force in North Carolina politics and "go where the sparks go," says the Rev. William Barber, head of the state NAACP and one of Moral Mondays' leaders.

"Seven years ago we started to prepare," Barber says. "We didn't know we were preparing for this moment. We didn't see this day coming."

Barber says the multiracial coalition behind Moral Mondays originally formed to push for increased voter registration, labor rights and more support for public education. It maintained its unity over the years because it knew other issues might arise and it wanted to be ready to hit the ground running.

"You have to do the hard work," he says. "You just don't helicopter in and make a speech. You have to build trust, talk with people and struggle with the issues."

The coalition is multiracial and multi-issue, crucial for any movement that wants to have broad appeal. It has the support of about 150 groups, including clergy, white college students and women's groups. Barber says he has received calls from people around the country who want to replicate Moral Mondays in other states.

He says the years of planning paid off when the Republican-led assembly provided the spark that helped Moral Mondays launch the "spontaneous" protests.

Barber's advice for movement builders: Don't wait for the right spark to organize. Do it now.

"No matter where you are now, now is the time to build coalitions," Barber says. "You do it now because when the moment comes, the only thing that will be able to save you is to be together."

2. Make Policy, Not Noise

They gave the nation a nifty slogan: "We are the 99%.'' But they haven't been heard from much since. Remember Occupy Wall Street? In 2011, a group of protesters occupied a park in New York City's financial district to protest income inequality and the growing power of financial institutions.

Occupy Wall Street protesters demonstrate

in New York City in October 2011.

Occupy Wall Street generated plenty of media coverage, but its largely faded from public attention. Yet the tea party, a conservative movement that arose in 2009 to protest government spending and debt, is still wielding influence in American public life.

Why does the tea party have more influence than Occupy Wall Street?

The tea party didn't just make noise; it put people in office, several political scientists and historians note.

Former Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin speaks to

a tea party crowd in Iowa in 2011.

"The tea party from the outset focused on winning elections and setting up a structure that could affect the political process," saysLarry Schweikart, co-author of "A Patriot's History of the United States."

"The Occupy Wall Street group only wanted to raise hell."

Successful movements just don't take it to the streets. They elect candidates, pass laws, set up institutions to raise money, train people and produce leaders, observers say.

The March on Washington, for example, had the charisma of King. But it also had the organizational genius of Bayard Rustin, a man whose attention to detail was so keen that people wryly noted he knew precisely how many portable toilets 250,000 marchers needed.

"Occupy used a very smart tactic -- sit in parks where people could join the protests," says Michael Kazin, a history professor at Georgetown University in Washington and an expert on social movements.

"At the same time, it was just a tactic," says Kazin, author of "American Dreamers: How the Left Changed a Nation."

"A tactic is not a movement. A lot of people got excited by the tactics, but they didn't have a second act."

People remember the March on Washington because it did have a second act. Civil rights leaders used the political pressure generated by the march and the subsequent assassination of President John F. Kennedy to pressure Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, historians say.

Still, they were also willing to compromise. And compromise is not glamorous. Failed movements are filled with stories of idealistic people who didn't make compromises. A successful movement, though, is filled with people who know that it is wise at times to compromise.

A compromise is what helped the March on Washington take flight, some historians say.

The original March on Washington wasn't supposed to be just about race but about economic issues as well. Organizers originally billed it as a march for "jobs and freedom."

Yet King and others de-emphasized the jobs' focus of the march because they thought it would jeopardize the passage of the pending civil rights bill, says Podair, the Lawrence University professor.

Talking about poverty and inequality at the 1963 march would have alienated potential Northern white supporters who would have seen such rhetoric as a ploy to redistribute money from the white middle class to blacks, Podair says.

Instead, organizers reassured them by focusing on King's dream of racial equality, he says.

"The reason they can get Northern whites to support the march is to say we're not going to touch your wallets," Podair says. "What we're going to do is ask the South to give African-Americans their political rights, something they should have done 100 years ago. But we're not going to redistribute income."

Those commemorating the 50th anniversary of King's speech during various events in Washington this month can learn from the leaders of the 1963 march, Podair says.

If the commemoration speeches are confined to racial issues such as the Trayvon Martin case, they won't be as powerful. But if they also talk about economic inequality, a major issue for white voters, they can also do what King originally did: cast a vision of America that appeals to all types of people.

"Sometimes it makes you feel good to preach to the choir," Podair says, "but after a while you have to go outside the church and find other people for your coalition."

3. Redefine the Meaning of Punishment

On July 6, 1892, 300 armed detectives confronted a group of unionized steelworkers who had been locked out of a steel mill in Homestead, Pennsylvania. The workers, who were striking for better wages at a time when people routinely worked 12-hour-per-day, six-day weeks, fought back with stones and guns. They eventually forced the armed detectives to surrender. Three workers and seven detectives died.

Sketch portraying striking steelworkers clashing with armed

detectives in Homestead, Pennsylvania, in 1892.

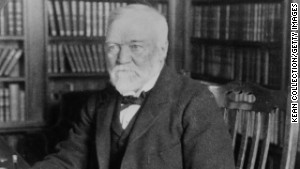

The Homestead Strike pitted striking workers

against steel titan Andrew Carnegie.

That confrontation is now known as the Homestead Strike. It pitted ordinary workers against steel titan Andrew Carnegie. Carnegie eventually crushed the worker's union, reduced wages and eliminated 500 jobs.

The past can inspire, yet it can also be intimidating. Some believe that contemporary Americans are too jaded and lazy to take the risks that 19th century workers at the Homestead Mill took. Can anyone envision striking fast-food workers fighting pitched battles against armed troops today?

One historian who has studied movements, though, says the belief that modern Americans lack the right stuff to rise up is "hogwash."

Sam Pizzigati is the author of "The Rich Don't Always Win," a book that traces how ordinary Americans in the first part of the 20th century rose up against plutocrats like Carnegie to create a vibrant middle class. Pizzigati calls that battle a "forgotten triumph."

When people experience enough pain, they will mobilize, says Pizzigati, a labor journalist and associate fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies.

"When people's situation becomes worse, when something changes and things that people took for granted have suddenly gone by the board and they see their position in society sinking, that's a powerful factor that can drive movements," Pizzigati says.

He points to the Great Depression as an example. In 1928, on the eve of the Great Depression, the top 1% of Americans took in 23.9% of the nation's income. The rich ruled. (In 2007, on the eve of the Great Recession, the 1% took in 23.5% of the nation's income, according to a University of California Berkeley study.)

President Franklin D. Roosevelt introduced a series

of reforms in the wake of the Great Depression.

In 20 years, though, a political movement arose that "totally" transformed the nation, he says. A "New Deal" coalition led by President Franklin D. Roosevelt introduced a series of reforms to protect Americans from the worst features of unrestrained capitalism. They created Social Security, strong banking regulations, raised taxes on the rich and protected the rights of unions to organize.

The New Deal is a classic example of the weak and powerless -- out of work Americans standing in bread lines -- triumphing over the fierce resistance of many of the wealthiest and most powerful elites in America who dismissed the New Deal as socialism and class warfare.

Pizzigati calls the New Deal an "egalitarian triumph."

He says most Americans in the "Roaring '20s" seemed to accept the economic inequality of that time. Few people thought anything could change, and the courts often ruled against any attempts to protect ordinary workers from workplace injuries and low pay.

Yet that same generation rose up to make the New Deal a reality, he says.

The lesson:

"As dark as things may seem at a given moment," he says, "things can change very rapidly when a social movement takes off."

Sometimes there is no cataclysmic event that inspires people to risk it all to join a movement. It can be the steady buildup of humiliation as people stew over being treated as second-class citizens.

Consider the gay and lesbian movement for equality. Palmer, author of "Healing the Heart of Democracy," says that for years, many gay and lesbians suffered in silence as people denigrated their humanity. That changed when a critical mass decided that the pain of "behaving on the outside in a way that contradicts the truth" that they held inside was too much.

"They redefined punishment," Palmer says.

"The redefinition goes like this: No punishment anyone can lay on me can possibly be any worse than the punishment I lay on myself by conspiring in my own diminishment."

4. Divide the Elites

It's easy to demonize "The Man" if you're talking with friends in a late-night dorm room rap session. But you're going to need "The Man" if you're going to beat "The Man," some historians say.

"Movements at some point have to get support from the elites," says Kazin, the Georgetown historian. "You need legitimation. You need some authorities to sort of say we may not support everything you're doing but basically you're in the right."

The civil rights movement got that support from the elites when the Democratic Party backed a civil rights bill during its convention in 1948, even though Southern white Democrats walked out, Kazin says.

Five years later, another group of elites lent their support to the movement. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the separate but equal doctrine was unconstitutional in Brown vs. Board of Education.

"The Supreme Court unanimously said that segregation was wrong," Kazin says. "They had an impact."

A movement, though, can't appeal to the altruism of elites to get their support. Elites help movements when they feel their own interests are threatened, says Pizzigati, author of "The Rich Don't Always Win."

That cold calculus among the rich is what made the New Deal possible, he says.

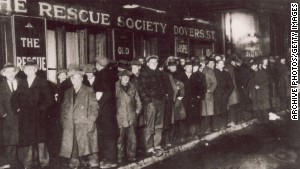

A bread line forms in New York City

during the Great Depression in 1929.

Economic conditions were so bad in America during the 1930s that many of the rich in America feared social upheaval, he says. The rich were being blamed for miserable economic conditions. People feared revolution. In 1932, the Communist Party held a rally in New York -- 60,000 people showed up as nervous police officers with machine guns looked on, Pizzigati says.

The people at the top feared that social instability would cause American society to crumble. They were people like Randolph Paul, a wealthy Wall Street tax lawyer who warned other wealthy Americans that they were courting disaster, Pizzigati says.

"Paul became such a fierce advocate for very high taxes on the American rich because he said that we could not tolerate the level of income inequality in the U.S., that it was going to bring the country down," Pizzigati says.

Other wealthy Americans brought into Paul's rationale. They allowed their taxes to go up. The Cold War helped as well. Communists said capitalism spawned yawning gaps between the rich and poor, and the American elite wanted to prove them wrong, Pizzigati says.

And they were willing to pay the price to make these changes possible, he says. By 1961, a married couple's income over $400,000 was taxed at a 91% rate, Pizzigati says.

The rich weren't as rich, but America's middle class was booming, Pizzigati says.

"We had a fundamental economic shift," Pizzigati says. "The plutocracy that had existed at the beginning of the 20th century had essentially disappeared. We went from a place that was two-thirds poor to two-thirds middle-class."

Could people without power spark such a movement today?

Palmer, author of "Healing the Heart of Democracy," believes they can. He is the founder of the Center for Courage & Renewal, a nonprofit that often works with activists through programs and retreats.

He says younger activists are more adept at coalition building.

"The young people today walk across lines of difference like they're not even there," he says. "My generation didn't walk across lines of sexual orientation, race or religion as easily as these kids. For a lot of them, it's not even noticed."

Still, there is one final lesson for anyone who wants to join a movement. Victory is fleeting and setbacks rare inevitable. At times, it can seem like it was all a waste.

King fought such a letdown later in his life.

Five years after he delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech, he gave a different one at a church in Memphis, Tennessee. The crowds weren't hanging onto his words like they once did. He had become unpopular because of his opposition to the war in Vietnam. Black militants scorned his nonviolent approach. And his plan to create a multiracial army of poor people to occupy Washington was floundering.

Yet he told the shouting audience at the Memphis church that "we as a people will get to the Promised Land."

King was assassinated the next day as he stood on the balcony of a motel chatting with his friends below.

He would not live to see his birthday turned into a national holiday. He wouldn't see the first black president elected. And he wouldn't see his four children become adults.

Those who give the most to a movement often don't see the rewards of their risk.

"We plant the seeds, but we don't know what the crop will look like," Palmer says.

That is perhaps the harshest lesson of all.

Source - CNN / John Blake

Wingspan Portfolio Advisors Blogspot