From a Book Review in the New York Times, "Parchman's Plantation," by James M. McPherson, on 28 April 1996 -- Authors are not always well served by the publicity releases their publishers send out. The Free Press acclaims '' 'Worse Than Slavery' '' as ''a window into a shocking and neglected century of despair . . . a forgotten era in black history.'' The story of despair may indeed be shocking to many readers, but it has been neither neglected by historians nor forgotten by African-Americans, whose music, art and folklore have preserved it in all its depressing but vital diversity.

|

| Worse Than Slavery: Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice, by David M. Oshinsky |

David M. Oshinsky, who teaches history at Rutgers University, would be the first to acknowledge his debt to historians like C. Vann Woodward, Vernon L. Wharton and many others whose work on the history of race relations in the South, and in Mississippi specifically, has made this field one of the most thoroughly cultivated in American historiography. Building on their studies of emancipation, Reconstruction and the post-Reconstruction ''New South,'' Mr. Oshinsky places the story of Mississippi's notorious Parchman prison farm in the context of sharecropping, convict leasing, lynching and the legalized segregation that replaced slavery. In vigorous, hard-hitting prose, he exposes the nature of the new system of race relations that was indeed worse in some ways than the kind abolished in 1865.

Yet this book makes clear that Parchman in its heyday as a prison farm was not the worst part of this new slavery. Actually, it may have been one of the least of the evils that characterized Mississippi's racial injustice. Mr. Oshinsky portrays Mississippi as consistently the nation's most violent state from the 1830's to the 1930's. Its frontier status in the early years of the antebellum cotton boom produced an astonishing crop of murders, duels, cuttings and gougings among white men. It also produced record crops of cotton grown by slaves working in a brutally repressive plantation system.

During Reconstruction the Ku Klux Klan and local rifle clubs murdered hundreds of freed slaves, now Republican voters, in the successful effort to make Mississippi safe for the Democratic Party. In the New South Mississippi led the nation ''in every imaginable kind of mob atrocity: most lynchings, most multiple lynchings, most lynchings of women, most lynchings without an arrest, most lynchings of a victim in police custody and most public support for the process itself.'' Nearly half a century later, in the 1930's, ''Mississippians earned less, killed more and died younger than other Americans. They were five times more likely to be illiterate than a Pennsylvanian and ten times more likely to take another person's life.''

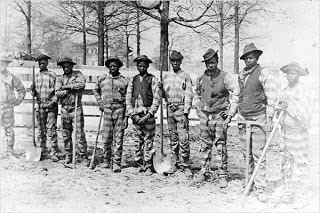

This culture of violence provided the setting for the most infamous form of criminal justice in American history, the convict leasing system that prevailed in most Southern states for a generation or more after emancipation. Not surprisingly, Mississippi invented convict leasing. Under slavery, black criminals had been punished on the plantation. Virtually the only jail inmates were whites. The Civil War destroyed many jails and penitentiaries, while emancipation more than doubled the free population. The crime wave and political violence that accompanied Reconstruction overwhelmed the few and inadequate jails. In desperation, Mississippi and other states turned to an expedient that quickly became an institution: the leasing of convicted criminals to private contractors, who paid a fee to the state and agreed to feed, clothe and shelter the convicts during their term of punishment.

But the motives of lessees were most emphatically not altruistic; they were in this business for profit. They used convicts to build railroads, to mine coal and iron, and to fell timber, make turpentine, clear land and grow cotton. Since nearly all leased convicts were black, few whites cared what happened to them. And if the supply of convicts fell below the demand, compliant legislators and country sheriffs stood ready to increase the supply. In 1876 the Mississippi legislature enacted the egregious ''pig law'' defining the theft of a farm animal or any property valued at $10 or more as grand larceny, punishable by up to five years in state prison. The convict population quadrupled overnight. Many contractors made fortunes from the cheap labor that they could exploit with impunity. Slaves had at least possessed the protection of their value as property; the lives of black convicts had no value in the eyes of whites. Mortality rates in convict camps rose to shocking levels. The death rate among convicts in Mississippi during the 1880's ranged from 9 to 16 percent annually. ''Not a single leased convict,'' Mr. Oshinsky notes, ''ever lived long enough to serve a sentence of 10 years or more.''

It was this system, not the Parchman prison, that the Southern reformer George Washington Cable described as ''worse than slavery.'' By the 1880's the barbarism of convict leasing had become an embarrassment even to white Mississippians. Reformers in all Southern states crusaded against the system. By the early 20th century they had succeeded in getting it abolished almost everywhere, though in several states it was replaced by state or county chain gangs -- not necessarily a great improvement.

In Mississippi, convict leasing was replaced by Parchman, a prison farm located on 20,000 acres of the world's richest cotton land, in the Yazoo-Mississippi delta. The best chapter in '' 'Worse Than Slavery' '' describes life and work for the inmates at Parchman from 1904 to the 1930's. During that time the proportion of black inmates declined from 90 to 70 percent. Whether Parchman was ''worse than slavery'' is not clear from Mr. Oshinsky's account. What is clear is that it was very much like slavery. The superintendent functioned like a slaveowner. The white guards (''sergeants'') were the overseers, and the ''trusties'' armed with shotguns and rifles resembled nothing so much as the black drivers on slave plantations. And Parchman was a huge plantation, growing thousands of bales of cotton, which produced a handsome profit for the state of Mississippi. Exploitation, violence, racism and repression characterized Parchman. Mr. Oshinsky reproduces the words of several blues songs that portray the Parchman experience with sad eloquence. But what emerges from Mr. Oshinsky's account is a set of ironies that he implicitly acknowledges but does not explicitly develop. Parchman was better than convict leasing. It was probably less brutal in its treatment of black inmates than the prisons or chain gangs of other Southern states. And in an odd twist, it may have been better in some respects than what the civil rights revolution of the 1960's forced it to become.

At that time, with in-your-face spite, Mississippi officials jailed hundreds of civil rights activists for a brief time at Parchman, including James Farmer and Stokely Carmichael. Their reports of dismal conditions focused a national spotlight on Parchman's dark corners that resulted in a class-action suit. A Federal district court ordered the state to reform, upgrade and desegregate the prison. Since 1970 it has been ''reformed.'' As a consequence, inmates who formerly worked from dawn to dusk in Parchman's cotton fields and fell into an exhausted sleep in the barracks now sit in their cells with little to do except vent their energy in deadly fights with one another. In desegregated barracks, black and white convicts who were once kept rigidly separated now prey on each other in organized gangs. ''The Federal court had shifted the balance of terror from the keepers to the inmates,'' Mr. Oshinsky writes, and in 1990 the Parchman emergency room treated the ''staggering number'' of 2,305 cases of assault.

Perhaps the ultimate irony was voiced by an elderly black inmate of almost 50 years at Parchman. In the old plantationlike prison, he said, he had ''the feeling that work counted for something . . . kept us tired and kept us together and made me feel better inside.'' But today, he added, ''I look around . . . and see a place that makes me sad.'' (source: The New York Times)

Wingspan Portfolio Advisors Blogspot